A Reflection on God’s Covenant, Justice, and LGBTQ Inclusion

By Kelly Paris

When Love and Doctrine Collide

As a new Christian, fresh to Scripture and community, I am eager to walk in truth. I am learning that God is love (1 John 4:8), that we are to act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly (Micah 6:8), and that Christians would be known by their love for one another (John 13:35). This is the Jesus I am coming to know.

One evening in a Christian small group, someone referenced the rainbow as God’s covenant sign in Genesis 9:13–17. Shortly after, they expressed sorrow that it had been “stolen” by a group they believed dishonor God. Their grief was real. I didn’t speak. I just listened.

Days later, I heard a pastor preach that the Hebrew word qeshet (קשת) actually refers to a war bow, which God “sets down” in the sky poetically showing that He is hanging up His weapon of judgment, symbolizing peace. It was that moment, a quiet question arose in my heart:

What if God allowed the rainbow to become a symbol for the LGBTQ community as protection over them?

This holy question began a deeper exploration of Scripture and cultural tradition. After all, God’s bow is a sign of restraint. A divine promise not to destroy, but to protect. Is it possible, the rainbow embraced by LGBTQ people, is a symbol to declare the same covenant promise: that God’s weapon remains laid down, His grace covering all humanity, including the LGBTQ community?

In this way, the rainbow could be seen as a sign of God’s ongoing protection and peace over people who have often faced debilitating human judgment and rejection. This assignment offered a framework to revisit my tension between faith, language, and human dignity. What I discovered was not a departure from theology, but a fuller, more loving understanding of it.

Film Summary: 1946 – The Mistranslation That Shifted a Culture

As part of this journey, I studied 1946: The Mistranslation That Shifted a Culture (Roggio, 2022), which proposes through archival records that the term “homosexual” did not appear in any Bible until the 1946 Revised Standard Version (RSV).

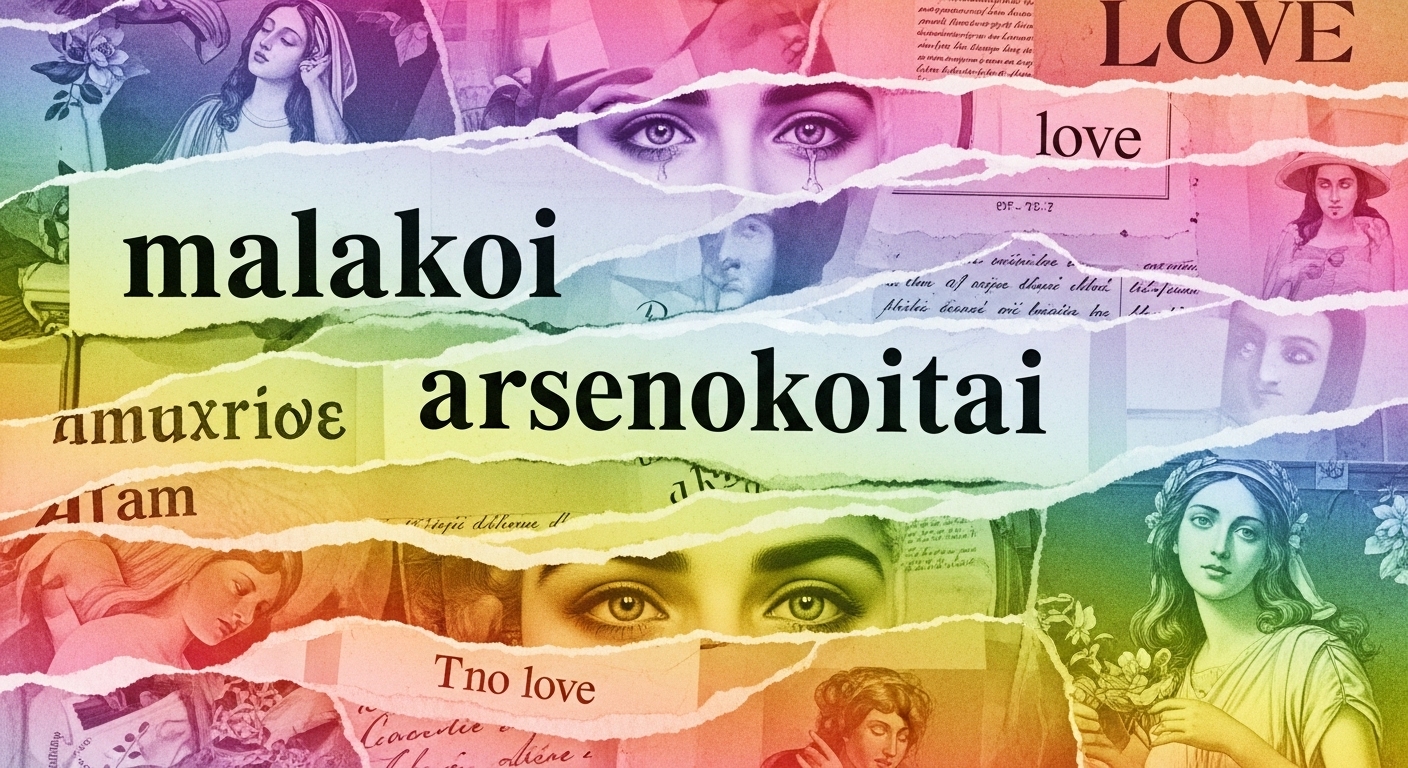

The film traces the mistranslation of two Greek words found in 1 Corinthians 6:9; malakoi and arsenokoitai.

Malakoi (μuαλακοί) – Literally means “soft.” Culturally, it referred to moral weakness or self-indulgence, not sexual orientation.

Arsenokoitai (ἀρσενοκοίται) – A rare compound term Paul may have coined. It likely referred to exploitative sexual acts of pederasty, temple prostitution, or coercive relationships; not consensual same-gender love.

The documentary argues that the RSV translation committee replaced these terms with “homosexuals,” thereby shifting the church’s posture from condemning abusive sexual behaviors to condemning LGBTQ identity itself (Roggio, 2022). The film uses archival footage, interviews, and committee letters to support this claim, including a 1959 letter from a seminary student to Dr. Weigle, the committee chair, showing that even members questioned the translation (Roggio, 2022).

However, traditional theologians contest this interpretation, asserting that arsenokoitai rightly condemns all same-sex acts (Gagnon, 2001). An academically responsible approach acknowledges both perspectives while recognizing the enormous impact a single translation decision has had on global Christian ethics.

Structurally, the film blends historical analysis with personal narrative and clearly aims for an affirming theology, which shapes its bias. Yet it raises urgent questions of justice and fidelity to language that scholars and Christians alike must continue to wrestle with (Brownson, 2013).

Deepening the Linguistic Analysis

The film transcript demonstrates that malakoi historically described “softness,” sometimes cowardice and decadence, but was not synonymous with orientation. Likewise, arsenokoitai appears fewer than 100 times in ancient literature, typically linked to exploitative sex or pederasty (Loader, 2013). These nuances matter. When translated broadly as “homosexuals,” they collapse centuries of layered meaning, conflating behavior with identity. This echoes what Sensoy and DiAngelo (2017) describe as the power of language to uphold oppression through false universals. The consequences, as highlighted in the film, are measurable: LGBTQ people excluded from Christian community, and vulnerable to spiritual and physical harm.

Reframing Sin: Identity vs. Behavior

Studying these Greek terms and the historical mistranslation challenged me to reconsider how I understand sin. The biblical witness, I believe, does not condemn someone for existing, but rather for exploitative or abusive acts (Gushee, 2017). This resonates with Ermine’s (2007) concept of an “ethical space,” where diverse truths can engage respectfully across difference. Within this ethical space, we might see LGBTQ Christians not as people needing correction, but as siblings in faith worthy of full belonging.

Drawing on Noddings’ (2006) ethic of care, I see how moral relationships require love without agenda. For too long, the Church has turned LGBTQ people away for who they are, while embracing others who struggle with sexual sin as still beloved. This contradiction is rooted in a theological error. If the fruit of the Spirit is the measure (Galatians 5:22–23), then a person’s love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, and self-control should be the test, not orientation. Brownson (2013) reminds us that biblical sexual ethics consistently elevate covenantal love and mutuality over domination or harm.

The Ongoing Wrestling

This journey has not resolved all my questions. I still grapple with what to do with Levitical codes, or Romans 1, which seem to denounce same-sex behavior. Loader (2013) and Vines (2014) have helped me explore these passages through the lens of cultural context, patriarchy, and power rather than modern LGBTQ relationships, which are grounded in love and consent. That reframing does not erase my tension, but it makes space for me to wrestle, in community, and under God’s wisdom. Here, Brookfield (2017) suggests that critical reflection means embracing our own discomfort to become more authentic educators and practitioners. I remain in that tension, and perhaps that is faithful.

Connecting to Course Theories and Personal Positionality

Throughout EDUC 5041, I have learned the importance of critically examining my own identity and power. As a straight, Christian, educated, upper-class mother and educator, I hold a position of power that demands reflexivity (McIntosh, 1988; Gorski, 2011). Ermine (2007) challenges me to see my voice as one among many, creating space rather than closing it. Integrating Banks’ (1998) multicultural framework, I can work to transform my practice from mere inclusion to true equity, where LGBTQ children and families are not just welcome but centered in their humanity. That shift requires consistent efforts to challenge deficit ideologies (Gorski, 2011) and to resist what Appiah (2005) calls “honor codes” that keep oppressive traditions alive.

Applying Sensoy and DiAngelo’s (2017) social justice principles, I also reflect on the ways my niceness, a polite, conflict-avoidant Christian posture has historically served to maintain systems of oppression. As a mother, this means ensuring my children see LGBTQ individuals as fully human, fully beloved, and not as sinfully rejected. As an educator, it means disrupting classroom scripts that privilege heteronormative family models and affirming all families and all students.

Professional and Community Implications

Beyond parenting and teaching, this transformation invites me to consider how church leadership, Christian schools, and Christian counseling might be reshaped.

- How might we structure youth programming so LGBTQ teens do not merely survive but flourish?

- How might lesson planning embed an ethic of care (Noddings, 2006) and principles of universal design (Johnson & Fox, 2003) to support every learner?

- How might we, as Christian educators, develop professional codes of conduct that explicitly name and resist LGBTQ discrimination, aligning practice with Micah 6:8’s call to do justice?

These remain open questions, but essential ones for me to keep exploring.

This reflection does not compromise my faith; it clarifies it. Scripture never calls us to cast out those we don’t understand. Instead, we are told:

“Love your neighbor as yourself.” – Mark 12:31

“Do not judge, or you too will be judged.” – Matthew 7:1

“Carry each other’s burdens.” – Galatians 6:2

God’s justice is His alone. Our instruction is clear: love and help one another.

Reclaiming the Rainbow

The rainbow is still God’s. And maybe, just maybe, it stretches across the sky as a whisper to every LGBTQ child who has been told they are beyond redemption:

“This is my child, whom I love; with [them] I am well pleased.” – Matthew 3:17

This isn’t a departure from Christian truth. It’s a return to it. A reclaiming of the rainbow as God’s covenant sign of protection and peace, even over those historically cast aside. Rather than seeing the rainbow as ‘stolen,’ perhaps we might see it as a renewed witness of God’s grace for all people. It invites us to reassert the rainbow’s deepest purpose: a divine promise of mercy that is inclusive, not exclusive. A truth that reclaims love as its highest ethic.

References

- Appiah, K. A. (2005). The ethics of identity. Princeton University Press.

- Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Brownson, J. V. (2013). Bible, gender, sexuality: Reframing the church’s debate on same-sex relationships. Eerdmans.

- Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1), 193–203. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ilj/article/view/27669

- Gagnon, R. (2001). The Bible and homosexual practice. Abingdon.

- Gorski, P. (2011). Unlearning deficit ideology and the scornful gaze. In R. Ahlquist, P. Gorski, & T. Montaño (Eds.), Assault on kids: How hyper-accountability, corporatization, deficit ideology, and Ruby Payne are destroying our schools (pp. 152–176). Peter Lang.

- Gushee, D. (2017). Changing our mind (3rd ed.). Read the Spirit Books.

- Johnson, D. M., & Fox, J. A. (2003). Creating curb cuts in the classroom: Adapting universal design principles to education. In J. L. Higbee (Ed.), Curriculum transformation and disability: Implementing universal design in higher education (pp. 17–34). University of Minnesota.

- Loader, W. (2013). Making sense of sex: Attitudes towards sexuality in early Jewish and Christian literature. Eerdmans.

- McIntosh, P. (1988). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Independent School, 49(2), 31–36.

- Noddings, N. (2006). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

- Roggio, S. (Director). (2022). 1946: The mistranslation that shifted a culture [Film]. 1946 The Movie, LLC. https://www.1946themovie.com/

- Sensoy, Ö., & DiAngelo, R. (2017). Is everyone really equal? An introduction to key concepts in social justice education (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

- Scripture citations throughout are drawn from various translations, including the NIV, ESV, and NRSV.

- Vines, M. (2014). God and the gay Christian. Convergent.